During the period between 900 BC and 700 BC, the political landscape of the ancient Near East was marked by shifting powers, inter-regional conflicts, and external interventions. The core states in this region, namely Egypt, Israel, Judah, and Assyria, played pivotal roles in shaping the era’s political dynamics. This period witnessed the rise and fall of powerful dynasties, including the 22nd Dynasty in Egypt, the divided kingdoms of Israel and Judah, and the expansion of the Assyrian Empire.

Egypt: The Fragmentation and the Rise of Kushite Power

In Egypt, the 22nd Dynasty ruled for nearly a century, but by around 838 BC, the kingdom faced internal strife. A political struggle emerged between two branches of the royal family. One faction controlled the northern regions around the Delta (in cities like Tanis and Bubastis), while the other held sway over the southern regions centered around Thebes and its powerful temple institutions. This division began under King Osorkon II and grew into a more significant rift over time. By the later years of King Sheshonq IV’s reign, a figure named “Badu Basit” declared himself king over Egypt from Thebes. However, this move marked a period of growing political instability.

The fragmentation within Egypt led to the rise of regional rulers who declared themselves kings over various territories, which weakened the central authority. By 750 BC, Egypt was divided once again into several smaller, regional sovereignties. During this period, external powers began to influence Egypt’s politics.

To the north, the Assyrian Kingdom, a rising power in the ancient Near East, began to extend its reach over the Levant and Egypt. Meanwhile, in the south, the Kingdom of Kush, based around the 4th Cataract in Napata (modern-day northern Sudan), looked to assert its influence over Egypt, particularly in the region of Thebes. The Kushite kings, whose rule was heavily tied to the cult of Amun in the Jebel Barkal region, saw an opportunity to expand their influence into Egypt, claiming religious legitimacy by invoking Amun’s name.

Around 750 BC, Piankhy, the Kushite king of Napata, launched a military campaign to assert his authority over Egypt. His primary goal was to protect and control the Karnak Temple complex in Thebes. The Kushite rulers were deeply affiliated with Egyptian religious practices, adopting Egyptian royal symbols, names, and architectural styles, including pyramid burials. The reign of Piankhy and his successors, such as King Taharqa, saw the expansion of the Kushite Kingdom from the 4th Cataract all the way to the Mediterranean coast, making it the largest Nubian kingdom in history.

King Taharqa, in particular, is known for his military campaigns in Egypt and Palestine. His reign was marked by efforts to push back Assyrian expansion in the region, and his name even appears in the Old Testament during his campaigns against Judah in 677 BC.

Israel and Judah: Divided Kingdoms and Assyrian Influence

The history of Israel and Judah during this period was characterized by political fragmentation and vulnerability to external powers. Following the reign of Solomon, the Kingdom of Israel split into two separate states: the northern kingdom of Israel, with its capital at Samaria, and the southern kingdom of Judah, with its capital in Jerusalem. The political turmoil within Israel and Judah set the stage for their eventual conquest.

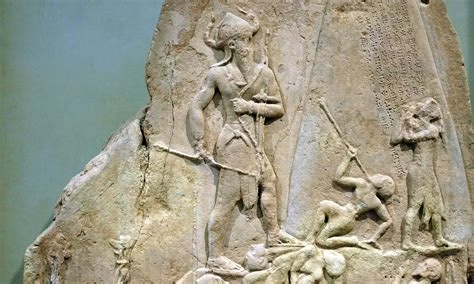

The Assyrian Empire, under rulers like Tiglath-Pileser III and Shalmaneser V, began to assert its dominance over the Levant, forcing Israel and Judah into submission. Israel, in particular, became a vassal state of Assyria, paying heavy tribute to avoid military invasion. An example of this is found in the famous Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, which depicts the tribute of Jehu, the king of Israel, brought to the Assyrian king. This tribute system was a key aspect of Assyrian foreign policy, which used coercion to maintain control over its vassals.

By 722 BC, the northern kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians after a prolonged siege of Samaria. The inhabitants of the city were exiled, marking the beginning of the Assyrian exile. Judah, on the other hand, managed to survive a little longer. King Hezekiah of Judah, who ruled during a time of Assyrian expansion, was forced to pay tribute to Assyria but also sought to navigate the complex political landscape by seeking help from Egypt.

The Assyrian Threat: Expanding Power and the Fall of Israel

The Assyrian Empire’s power continued to grow throughout the 8th century BC. During the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC), the Assyrians aggressively expanded into the Levant, pushing their influence into Israel and Judah. In 752 BC, the king of Israel, Menahem, paid a heavy tribute to Assyria to maintain his throne, a practice that continued under subsequent kings. However, the Assyrians had increasingly high demands, and by the time of King Hoshea of Israel (732–722 BC), the Assyrian pressure became unbearable.

Hoshea attempted to break free from Assyrian control by appealing to Egypt for help. However, the Assyrians discovered this conspiracy and punished Israel, leading to the fall of Samaria in 722 BC. This event marked the end of the northern kingdom of Israel.

Meanwhile, in Judah, King Hezekiah (715–686 BC) struggled to maintain his kingdom’s independence in the face of Assyrian aggression. The Assyrian king, Sennacherib (705–681 BC), launched several campaigns into Judah, eventually laying siege to Jerusalem. Hezekiah, facing imminent defeat, sought divine intervention, and according to the Biblical narrative, the Assyrian army was struck down by an angel, forcing Sennacherib to retreat.

The Decline of Assyria and the Rise of Babylon

The later years of the 8th century BC saw the decline of Assyria’s power. After the death of its last great king, Ashurbanipal (668 BC), the Assyrian Empire began to crumble. In 612 BC, the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, fell to a coalition of Babylonians and Medes, marking the end of the Assyrian Empire. However, before its collapse, Assyria had left a lasting imprint on the political landscape of the ancient Near East.

Following the fall of Nineveh, Egypt briefly reasserted itself as a regional power under the 26th Dynasty, based in Sais. However, Egypt’s resurgence was short-lived. In 605 BC, the Babylonians under King Nebuchadnezzar II defeated the Egyptian army at the Battle of Carchemish, solidifying Babylon’s dominance over the region and paving the way for the eventual fall of Judah to the Babylonians.

The End of Judah and the Rise of Babylonian Influence

In the final years of Judah, King Josiah (640–609 BC) attempted to resist Egypt’s influence. In 609 BC, Pharaoh Necho II of Egypt marched to aid the remnants of the Assyrian Empire in northern Syria, but Josiah sought to prevent this. The two armies met at Megiddo, where Josiah was killed in battle. His death marked the end of Judah’s brief period of independence.

Josiah’s successor, Jehoiakim, was installed by Pharaoh Necho and was forced to pay tribute to Egypt. However, the shifting tides of power eventually led Judah to align itself with Babylon after Egypt’s defeat at Carchemish. This change in allegiance ultimately led to Judah’s conquest by the Babylonians in 586 BC, bringing an end to the Kingdom of Judah and the beginning of the Babylonian Exile.

Conclusion

The political topography of the ancient Near East between 900 BC and 700 BC was shaped by the rise of powerful empires, internal divisions within kingdoms, and the constant interplay between regional powers. Egypt, Israel, Judah, and Assyria all vied for dominance in a landscape defined by military conquest, religious influence, and shifting allegiances. The period culminated in the rise of the Assyrian Empire, followed by its eventual decline, leaving the stage set for the rise of Babylon as the new dominant power in the region.